If Gary Friedman excels at one thing, it may well be executing the seemingly impossible. “Any new idea, any great idea, you’re going to have a thousand people tell you it can’t be done for every one person who might think it’s a good idea,” he tells me one afternoon in November, gesturing toward the Napa Valley sky. He’s talking specifically about the glass atrium of his newest restaurant—a glittering, 54-seat, full-service outpost in wine country—but the sentiment will hold true across most topics we discuss. “Nobody thought I could have 100-year-old olive trees work inside a restaurant, because to do that, you have to build bunkers in the ground with enough dirt and irrigation to keep them alive—and a glass roof so they get enough sunlight.”

The roof proved trickiest, unlikely to pass California’s stringent energy code. After more than a year of being told he’d have to settle for a much smaller skylight, Friedman had a revelation at a real estate conference in Las Vegas. He’d returned to his hotel to see the afternoon sun streaming, and noticed that the room wasn’t too hot. He looked outside; the building, and many of the hotels around it, were all made of glass. “This is a 110-degree day in Las Vegas, but somehow they’re not blowing up the electrical systems,” he recalls. He asked his team to chase down the glass manufacturers, he explains, as we sit under a canopy of his hard-won olive trees in an atrium built of the same slightly reflective glass that takes in sunlight without the heat.

I had flown out to Yountville—a picturesque vacation town with only 3,000 full-time residents, a vineyard-lined 10-minute drive from downtown Napa perhaps best known as the home of Thomas Keller’s renowned restaurant The French Laundry—where Friedman opened the newest RH outpost in October. A five-building enclave, RH Yountville is connected by boxwood-lined allées of decomposed granite and bounded by oversize roaring fireplaces that ward off the evening chill. Crystal chandeliers hang overhead, tucked amidst those olive trees—an arresting sight indoors. During the day, sunlight creates dappled shadows of foliage on the tabletops; at night, the space glows, alluring and romantic. “This couldn’t just be any restaurant,” says Friedman. “We had to do something extraordinary.” It’s another statement that I soon realize applies to much more than just this space.

But RH Yountville almost wasn’t. Napa Valley towns are known for their reluctance to welcome chain retailers, and the project took four years to complete. (Although no such law exists on the books in Yountville, a 1996 “no-formula” ordinance in neighboring Calistoga sets the tone, challenging major retailers to build something special and unique.) Friedman himself went to present the site plan at a city council meeting. “There were a lot of people thinking, We’re not going to let this retail store into the Napa Valley,” he recalls. “So I said, ‘Look, let’s start with the fact that we don’t build stores. We build inspiring spaces that blur the lines between home and hospitality.’”

In the face of the slew of experiential “museums” that are gaining popularity, particularly in New York—hollow, 2-D fantasies dedicated to rosé, ice cream and rainbow hues that seem to exist almost exclusively for product placement and Instagram likes—RH’s new galleries upend the notion of what it means to open a store. Because, despite the small “RH” on the facade, Friedman was true to his word: In RH Yountville, he has created an experience that hardly feels like it is selling anything at all.

+ + +

Friedman has immense belief in the power of physical stores, and that they will be the most cost-effective way to scale a brand. “The simplifying—and incorrect—assumption is that you can make more money online, right? Totally untrue,” he says. “Amazon, that’s a marketplace. They’re in the web services business, they’re in multiple businesses. There has not been one online-only brand that’s reached $1 billion [in revenue] and made any money—most haven’t reached even $100 million and made money. Warby Parker couldn’t get over $100 million without building stores, and now all of their growth is coming from those stores.”

He holds up his phone. “A website is what I call an invisible store,” he says. “You don’t see it, you don’t walk by it, you don’t walk into it. The only way to get people to come to your online store is to advertise it. A lot of people believe that the web is going to be more profitable because you don’t have to build physical stores, but they’re not doing the math that you have to spend all this [money on] digital advertising. If someone tells me about you, or if I see an ad for you, maybe I’ll click on it. But if you come to something like RH Yountville, you’ll see it and you’ll remember it. If you do wonderful physical spaces and stores, they make money. Internet businesses don’t launch and immediately make money.”

He points to his phone again. “The web is the most democratic channel: The smallest retailer in the world looks the same as the largest on a screen. But here”—he gestures around the Yountville restaurant—“you can see the size and scale of the compound. Or if you see one of our large galleries, you’re like, ‘Whoa, there must be a lot in there.’ But if you look at a website, you don’t know how much is in there. You would have to click 10,000 times to know how large our assortment is.”

RH Yountville’s two gallery spaces combined total 5,000 square feet, offering an abridged collection of the RH look and feel. There are no cash-and-carry items for sale, but Friedman has no qualms about opening galleries across the country that make selling secondary. “Most people shop for furniture once every 10 to 20 years,” he says—an out-of-sight, out-of-mind category for the average consumer. “But we eat every day, so by having people come eat with us—if we have inspiring design and compelling product, they might say, ‘This is beautiful.’ But if they never saw it, they never would have thought about it.”

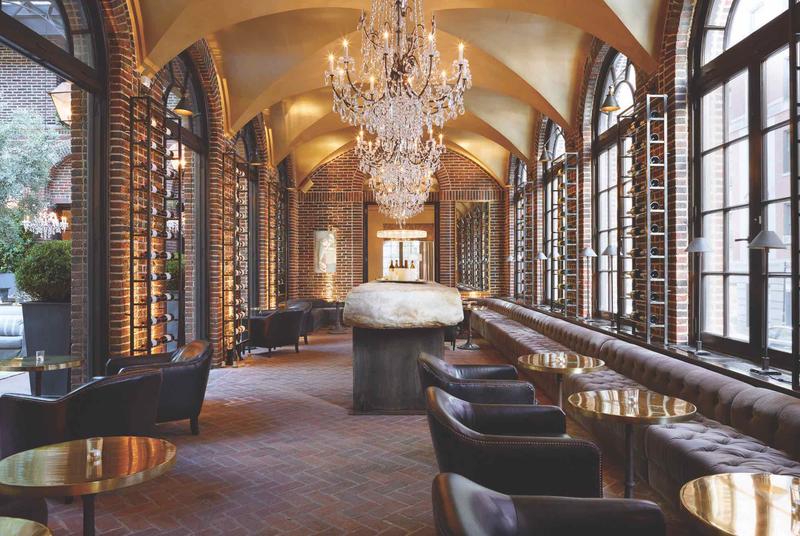

Friedman calls places like Yountville “billboard markets”—locations that don’t have enough of a population to support a full-fledged store, but where there is a high concentration of affluent consumers visiting for vacation. (The Napa Valley is the second-biggest tourist destination in California.) “People come here for the food and the wine, so this space is all about food, wine, art and design, and in that order,” he says. It’s true—of RH Yountville’s two street-facing buildings, one is the restaurant; the other is a wine bar housed in a restored 1904 structure, formerly a by-appointment tasting room called Ma(i)sonry. “Visitors can also experience the little galleries, but this—the food and wine—is why they come. It would have been dumb to just do a store here; no one’s coming to Napa Valley to shop for home furnishings. This is a different way to have people connect with the brand.”

One way customers won’t interact with RH is on social media. As retail brands at all levels of the market pour money into beefing up their online presence, RH doesn’t have a presence at all. “Our focus is on doing great work and letting the world talk about us,” says Friedman. If no one’s talking about the brand online, he reasons, the work’s not good enough—which is all the more reason to invest in the products rather than “posting online about ourselves.” When talking about eschewing social media, Friedman uses the word authenticity. He’s laser-focused on communicating what the brand is about in the spaces his team creates—on showing, rather than telling.

A cursory scroll of #restorationhardware seems to prove him right—people are talking (and posting) about RH. “We don’t have Instagram, yet we are the most-Instagrammed brand in our industry. We don’t have Twitter, yet ‘Rain Room’ was the most-tweeted art exhibit ever. [RH commissioned the immersive installation from British art collective Random International; it debuted at London’s Barbican Centre in 2012 and was later loaned to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, then gifted to Los Angeles County Museum of Art.] We don’t have Pinterest, but we are the most-pinned home brand,” he asserts. “We believe it’s not what we say, it’s what we do that defines us.”

On an earnings call in September, Friedman outlined the scope of the brand’s vision and value. “When you step back and consider: One, we are building a brand with no peer; two, we are creating a customer experience that cannot be replicated online; and three, we have total control of our brand from concept to customer, you realize what we are building is extremely rare in today’s retail landscape, and we would argue, will also prove to be equally valuable,” he said.

“If you think about great taste and great design, it’s very rare,” he tells me two months later. “There are those with taste and no scale, and those with scale but no taste. We are trying to scale taste.”

+ + +

After being passed over for the CEO role at Williams-Sonoma, Friedman arrived at RH in 2001. “My heart was broken and I felt trust was lost,” he says. Restoration Hardware, as it was still called then, was “the right place at the right time” for Friedman’s career, but it was also a challenge: The brand—which primarily sold home fittings and fixtures, novelty gadgets and gifts—was unprofitable, posting mounting losses in 1999 and 2000, and on the verge of bankruptcy. (“I had to raise money three times in the first year to keep the company afloat,” says Friedman today.)

If you think about great taste and great design, it’s very rare. We are trying to scale taste.

If you think about great taste and great design, it’s very rare. We are trying to scale taste.

“You’ve got to remember what Restoration Hardware looked like back then,” says Warren Shoulberg, a retailing and home furnishings expert (and Business of Home contributor) who was editor of Home Furnishings News when Friedman took the helm at the retailer. “They were in malls, and the product assortment was heavy on the ‘restoration’—paint, doorknobs and the like. There was some furniture, which was all mission style, and at Christmas, they’d load it up with a lot of impulse items. But if you’re selling a lot of $5.99 yo-yos, the math just doesn’t work with those mall rents.”

Friedman spent his first decade growing and retooling the brand’s product assortment, which debuted in 2008 at a much higher price point—and in the midst of the recession, as stand-alone stores like Williams-Sonoma Home shuttered, no less. “It was really high-end design stuff for retail,” recalls Shoulberg. “Everyone was dumbing down their stuff and getting promotional. I asked him then: ‘Why are you going so upscale?’ He said, ‘If we’re going to go under, we’re going to go under in style.’ RH really made a statement—they said, ‘There is a customer for this, even in these hard times.’ That was the start of the change.”

The goal was to size the brand’s offerings to the potential of the market, not limited by the size of its existing stores. “The old stores were built for a different company,” says Friedman of the 6,000-square-foot spaces dotted across the country, which show less than 10 percent of the company’s product. The brand has debuted 19 new galleries since 2011, including five (in Chicago, West Palm Beach, Nashville, Toronto, and now New York) with a food and beverage program incorporated into the retail space; Yountville is the brand’s first stand-alone restaurant. As leases expire, the company is strategically expanding its real estate footprint, with plans to open five to seven galleries each year.

To showcase all of the product that didn’t fit into stores, Friedman unveiled RH’s version of the catalog, called the Source Book, in 2009. Today, the catalogs—one each for Interiors, Modern, Outdoor, Rugs, Baby & Child, and Teen—regularly clock in at a combined 2,500 pages. (“In most markets, Source Books are the only physical manifestation of our brand,” says Friedman.) Still, building new, larger retail stores across the country remains the most important driver of growth. “Products that are showed at retail sell 100 to 150 percent better than products that are only online or in our catalog. We’re just now unlocking the value of the assortment.”

But Friedman admits that his strategy of investing in massive stores and catalogs, and saying no to Amazon (“We believe that brands with more control will become more valuable”) and Instagram is unconventional—and not always popular with shareholders. In early 2017, the company took the market by surprise, announcing that RH had borrowed heavily to repurchase 48 percent of its own shares, for $1 billion. Shares then tripled in price—a crushing blow to the bevy of short-sellers who had helped drive down the stock price by nearly 80 percent, and who had been betting on its continued decline. (“We said, ‘Look, if they don’t want to bet on us, we’ll bet on ourselves,’” Friedman told CNBC’s Mad Money host, Jim Cramer, at the time.) But by an earnings call in April 2018, shares had tumbled 25 percent again, suggesting that many on Wall Street were still apprehensive about the company’s finances. And by October, the company announced yet another share repurchase program—this time $700 million, which would represent about 25 percent of all outstanding shares.

“There are plenty of skeptics out there,” says Shoulberg. “The investment community doesn’t think the market is big enough to support the kind of business he’s talking about. Maybe stores in New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Dallas and West Palm Beach—but you can’t put one in Indianapolis, they say.”

Friedman has outlined a vision to build out more RH stores across the country in the likeness of its galleries—and he continues to insist that the company’s shares are undervalued in the market, framing repurchases as a vote of his confidence in RH’s future. “When the stock was in the toilet, $20 or $30 a share, they were all saying, ‘We told you so,’” says Shoulberg. “But Gary was saying, ‘No, we’re working it out, and you’ll be sorry.’ There are a lot of businesspeople who have said that and are out of jobs, but he’s stuck with it. Everyone in retail is so afraid of taking any risk right now, but he’s doing it.”

At press time, RH had just announced its third-quarter earnings, beating the market estimate of $1.27 per share by 36 percent—a triumphant showing largely based on the success of its galleries and restaurant programs. Friedman remains unflaggingly confident in RH’s direction, downplaying the impact of tariffs or a slowing housing market on the company’s growth. What don’t short sellers understand about the business? “Everything,” he says. “Leaders are generally misunderstood because leading is about changing things, and change makes people uncomfortable. We have to be comfortable making everyone else uncomfortable—that’s when we know we’re on the right track.”

+ + +

When RH first went private in 2008, Friedman’s private equity partners brought in McKinsey analysts to evaluate the company’s strategy. “They did customer research and said, ‘You don’t have the authority to get into the baby and child business,’” he recalls. “I said, ‘Why would we think the customer would give us that authority when we’ve never sold that product? Maybe if we do something extraordinary, they would shop with us.’” That thinking—the notion that the ideas of the future don’t exist in the past—underpins much of Friedman’s thinking about innovation. (Friedman would ultimately take the company public again in 2012; he is the company’s largest shareholder.)

Emotional value is the key metric Friedman has used to build RH’s products and programming. “What I’ve seen over the years are ideas that had high financial value but only moderate emotional or strategic value, where the financial value was never realized,” he tells me. “You can come up with a $100 million idea, but if no one really believes in it or brings it to life, that becomes a $2 million idea because it’s never executed well.” The same phenomenon, he says, is true in reverse: “Things that have high emotional and strategic value but only moderate financial value have always become a financially bigger idea,” he says. “Any great work, a great product, or a great outcome, there’s generally someone behind it who cares deeply about it, is willing to get knocked down 10 times and get up 11, sweat the details, keep obsessing about it, keep iterating it until it is insanely great.”

In the corner booth of the RH Yountville restaurant’s glass atrium, Friedman orders the shaved rib-eye sandwich and expands on how the space came to be. “We try to build inspiring spaces that ignite the human spirit and make people dream,” he says—and that’s what he told the folks gathered at the local town hall. He’d written a short speech about how, in a location renowned for its food and wine, he would build a space where Napa Valley visitors could experience the brand in an authentic way that reflected the local culture. RH would do its part, he insisted, to ensure that the retail side of the business was secondary, with two small galleries tucked in the back and no on-site shopping to speak of. Friedman showed videos of RH Chicago and RH Boston, and the crowd softened. “We had proof of the kind of work that we were doing, and people got it.”

RH no longer builds retail stores, Friedman often says. Instead, the brand has prioritized building spaces that are more home-like, awash in natural light and fresh air, with garden courtyards and rooftop parks. Its integration of restaurants was a logical extension of that thinking. “If you’re going to have someone in your home, you would offer them something to eat, something to drink—you would be hospitable,” he says. “We’re not the first ones to put a restaurant in a retail store, but we are the first to seamlessly integrate one into a retail experience.”

In 2011, RH instituted a membership program that gives customers a 25 percent discount on all merchandise and complimentary access to its in-house interior designers for an annual fee of $100. “The real key is to move away from a chaotic, promotional model of having these sales all the time, to simplify the business for our customers and ourselves,’” explains Friedman. (Ninety-five percent of all sales currently come from the company’s roster of some 405,000 members.) “It has smoothed out our business. We can buy the inventory correctly, not all the time, but it’s better for our vendors, better for our business, and we can offer better value.”

Today, two-thirds of the company’s business comes from interior designers: half internal, half independent. The trade is also the fastest-growing part of the business—growth Friedman attributes to the brand’s expansive new stores and the consistent discount. “They’re not just buying products, they’re working on projects,” he says. “It might take five months for them to buy all the stuff for it, so why force them to go, ‘Oh, they’re having a lighting sale right now, so hurry up and buy all the lighting!’ Why create all this chaos for everybody?”

+ + +

Friedman first started thinking about integrating retail and hospitality more than 20 years ago, when he first stayed at the Hôtel Costes in Paris. Enchanted by the restaurant housed in the hotel’s central courtyard—“There’s always this energy, this vibe, where people love to be in the space, that I’ve never seen replicated anywhere”—he began mulling over the elements that made the experience so unique.

On a 2011 real estate trip to Chicago with RH’s retail team, Friedman outlined his vision for the brand to a group of brokers and local developers. “I tried to articulate that we are obsessed with great architecture, whether we find it and adapt it, or build it.” A young man at the end of the table suggested a historic building called the Three Arts Club, but was quickly shot down by the rest of the brokers in the room. After an uninspired day touring what he calls “the usual suspects,” Friedman took the young man aside and said he wanted to see the club he had mentioned. “It needed a lot of work, but it was truly magical,” he says of seeing the building—a Holabird & Roche–designed terra cotta structure in a residential section of Chicago’s tony Gold Coast—for the first time. As a man in a long cashmere coat and an Hermès scarf walked by with a well-coiffed poodle, Friedman turned to RH’s president and chief creative officer Eri Chaya and said, “This is it.”

A month before, Friedman had taken his 9-year-old daughter on a spring break trip to Paris. (With a broken arm, she was unable to go skiing with her mother and twin sister; she told her dad that she had been dreaming of Paris after reading about it in a book at school, so he brought her there, he explains as he shows me a photo of them in the restaurant at the Hôtel Costes.) When he walked into the Three Arts Club, its similarities to his beloved hotel were all the more striking. “I see the courtyard, laid out almost exactly like the Hôtel Costes, with beautiful arches, and I said, ‘We have to do this.’ Which is a bad thing to say with the developers in tow, right? I’m losing all my negotiating leverage. But I knew instantly.”

Construction was soon underway—an immense preservation effort led by renowned architect Jim Gillam of the St. Helena, California–based firm Backen, Gillam & Kroeger, who has been shaping RH’s stores for nearly a decade. That left Friedman’s team only three and a half months to find a hospitality partner and get the restaurant open. “All the restaurateurs [we talked to] said they could open a little light-serve thing, and then maybe open a restaurant in six months,” says Friedman. His team told him that there was one guy in Chicago who thought he could do it: Brendan Sodikoff, founder of celebrated Chicago-based Hogsalt Hospitality, the upstart group that put itself on the map with Gilt Bar in 2010. “I google him and I’m watching some of his videos, and I really loved how deeply he thought about what he did,” recalls Friedman. “Plus, he wore T-shirts, so I knew he didn’t take himself too seriously.”

Friedman and his team traveled to Chicago to meet several local potential partners. But when it came time to tour Hogsalt’s establishments, the RH team spent an entire day not with Sodikoff, but with his director of hospitality, Ryan Wagner. After six restaurant visits, they finally met Sodikoff at Bavette’s, a lauded steakhouse and the last stop of the night. Sodikoff introduced himself briefly, showed the group to their table, and said he’d join them shortly. At first, Friedman was stymied. “We’re eating, and then I notice that Brendan is sitting [across the room] talking to Ryan,” he remembers. “That son of a bitch had been shaking me down all day, having Ryan figure out if I’m worth working with. I’m thinking, I like this guy. And when he finally comes over to meet with us, we really connect.”

The feeling was mutual, though Sodikoff had his reservations about the challenge. “Originally, I tried to talk them out of it—not once, but three or four times,” he admits. “Hospitality takes thousands of touches and a tremendous amount of effort, not on a daily basis, but on a minute-to-minute basis.” When the group met the next morning to tour the Three Arts Club, then a bustling construction site, Sodikoff brought the famous doughnuts from his award-winning Doughnut Vault, a move that did not go unnoticed by Friedman. (“I have such a weakness for doughnuts,” he admits as he’s telling the story. “Sometimes, in the middle of the night, I’ll go on a doughnut bender. It’ll be 1 o’clock in the morning, and I’ll actually drive into San Francisco, to this little neighborhood I grew up in, to go to this doughnut shop that’s been there for probably 100 years. If you go after midnight, the glazed doughnuts that come out are super fresh.”) Though Sodikoff had been approached for collaborations before, he always felt like his would-be partners didn’t have enough of a grasp on the complexities of opening a restaurant. “But [at that meeting], I saw Gary really listening to what I was saying,” he says.

On the plane back to California, Friedman’s team took 45 minutes to write down their thoughts about all of the potential partners, then gathered near the front of the plane. In team recaps like this, Friedman is careful to speak last. One by one, employees shared their impressions. It was 11 o’clock at night, but the meeting continued; their waiting cars surrounding the plane on the tarmac. His team had been wowed by another A-list chef, but Friedman surprised them all when it was finally his turn to speak. “I said, so-and-so is where it’s at, but Brendan Sodikoff is where it’s going.”

The early collaboration included adjusting the renovation of the Three Arts Club to make more room for the restaurant’s back of house. “We thought we’d do more than one [restaurant] if it worked,” says Friedman. “If nobody showed up, we’d do one.” But it worked—and then some. “What I thought might be a few hundred people on a good day turned into thousands,” says Sodikoff of the restaurant’s immediate success. RH Chicago seats upwards of 1,300 patrons a day—and that’s in a store that closes at 7 o’clock. “We’re closing when most restaurants are just getting their prime spots,” he says. The initial menu was driven by the space’s unconventional daytime hours—especially given Chicago’s cold and inclement winters, the sunlight streaming into the atrium that houses the dining room provides an outdoor feel unrivaled in town. “Some restaurants want to challenge the diner, or their intent is to make the diner uncomfortable by trying new things, but we’re the opposite,” says Sodikoff of his menu of classic dishes with a slight nod to RH’s California roots. “We want to provide you with timeless food options you can really relate to, provide an exceptional experience that you remember.”

The Chicago partnership with Sodikoff worked so well that RH brought the restaurateur on board as president of RH Hospitality. (Although Sodikoff technically splits his time 50–50 between Hogsalt and RH, his work for the two companies has become increasingly intertwined—but more on that later.) Friedman and Sodikoff recently spent the day together to celebrate the three-year anniversary of their collaboration, driving to Yountville and back for a recap and brainstorming session over lunch. “I’m so thankful,” says Friedman of the relationship. “Brendan’s so obsessed, so singular about what he does, and he’s such a deep thinker. He’s one of the most intelligent human beings I’ve ever met. He doesn’t speak as much as me, but when he speaks, you’re like, ‘Fuck, that was smart.’ I always feel like I learn something when I’m with him.”

For Sodikoff, working with RH is an opportunity to create spaces that would defy logic in a freestanding restaurant. “The cost per square foot to build it as a restaurant is not sustainable, but the cost per square foot, when added into the whole—less than 10 percent of the total square footage of the gallery—is only fractionally greater,” he explains. “That difference really allows us to do things that just astonish people: the glass roofs, the trees inside—these are things you don’t do! There’s a level of astonishment people have when they get to participate in this environment.” The RH spaces also don’t have to maximize seating the way a stand-alone restaurant might. “If RH Chicago was just a restaurant, I could fit an additional 50 seats,” says Sodikoff, laughing. Instead, there’s a rigorous balance and symmetry within each restaurant space. “Everything is lined up for the room to be at its best,” he says. (In another unconventional move, several of the hospitality programs, including those in West Palm Beach and New York, feature a rooftop restaurant—a strategy that initially felt risky, given most restaurants’ dependence on foot traffic.) “I had a hard time with how [these spaces] would manifest into a sustainable business at first, but the reality is that it works because people love being there so much. I’ve learned that if you focus on being great, on doing something exceptional—typically, there will always be a way to monetize the exceptional."

If you see one of our large galleries, you’re like, ‘Whoa, there must be a lot in there.’ But if you look at a website, you don’t know how much is in there. You would have to click 10,000 times to know how large our assortment is.

If you see one of our large galleries, you’re like, ‘Whoa, there must be a lot in there.’ But if you look at a website, you don’t know how much is in there. You would have to click 10,000 times to know how large our assortment is.

Sodikoff’s fingerprint extends far beyond each restaurant’s menu; he’s also integral to the development of the hospitality program that powers each gallery. RH builds centers off-site to train hundreds of people before a gallery opens, and then continue training on-site. For some jobs, like the baristas, training is six to eight weeks before, and another two months after, an opening. (In comparison, a coffee chain’s typical training period is about two weeks.) “It’s a huge commitment to quality that’s not typical of any hospitality program I’ve ever seen,” says Sodikoff. The focus on hospitality extends to team members outside of the food and beverage programs, as well. “We hold seminars for gallery leaders on our general vision so that we’re all speaking the same language. Something as simple as, if it’s cold and raining 10 minutes before opening, but someone is waiting outside, say, ‘How are you? Would you like to get out of the rain? Come in.’ We’re taking a real human point of view.”

But initial buzz aside, can RH’s galleries sustain the hype? If RH Chicago is any indication, the answer is yes. “We thought it was going to do $800,000, maybe $1 million [annually]—and then we opened, and it was packed,” says Friedman. In the first year, the restaurant brought in $5 million; three years later, it’s still hitting $6 million in revenue each year. “Every Saturday and Sunday, there’s a line [of people] around the corner waiting to get a table for brunch,” adds Friedman. “We’ve had over 60 marriage proposals in our restaurant. You can’t make that shit up. People getting proposed to in a furniture store, are you kidding me?”

Future flagship galleries will all incorporate a hospitality element. “We’re marching toward that,” says Sodikoff. “As we’ve built all these different models, we understand what we like more and why. The next step is to see how we can fit hospitality into a slightly smaller footprint—in markets that warrant a 30,000- or 40,000-square-foot store, not one that’s 70,000 square feet, for example—and still provide the same level of warmth and generosity. The more we open and the more we integrate these spaces, the more we learn.”

RH’s least successful hospitality venture thus far has been the Toronto gallery, which opened in 2017 as the anchor to a new, high-volume shopping area in town. Other stores have been slow to come in, and Friedman estimates that at least a football field separates the gallery from the next open retail store. At $4 million last year, the store is exceeding expectations—but compared to Chicago’s $6 million, it looks like it underperforms. Friedman seems less troubled by the store’s current state than he is interested in what it says about the company’s plans for the future. “It’ll keep filling, it’ll do well,” he says of the shopping center. “But also, you have to think, Can you build any stores in malls? Is that where we really want to be? Chicago really proved we could go off the beaten path.”

+ + +

Friedman’s rise to retail glory is an unlikely story, at best: After his father died when he was 5 years old, he lived in a series of small apartments with his mother, who had bipolar schizophrenia (“In her best year, she made $5,000,” he says), moving frequently because they kept getting evicted. “I’m the least likely guy to be doing what I’m doing,” he admits. “I grew up thinking rich people had color TVs. I never grew up around design—never lived in a house or had any furniture. I didn’t do well in school, and couldn’t really read, because I learned visually.” After completing his first year at Santa Rosa Junior College with a D average, a counselor told him that he was wasting taxpayer money. “I was a stock boy at the Gap, and I thought, I’m really good at folding clothes, and they’re really nice—they like me. I’m just going to do this.”

From stock boy to sales person, store manager and district manager, Friedman excelled at merchandising at the Gap. He attracted the attention of retail giant Mickey Drexler, who was responsible for the Gap’s widespread popularity in the 1990s, before turning J.Crew into a cultural phenomenon, and by the time Friedman left the Gap after 11 years, he was overseeing 63 stores in Southern California as the brand’s regional manager. In 1988, he went to work for another retail industry legend, Howard Lester, who was 12 years into transforming Williams-Sonoma from a four-store regional brand with a promising catalog business into a several-billion-dollar empire. “Both were tremendous entrepreneurs and innovators who challenged the status quo in their industries,” says Friedman of Drexler and Lester. “Both took a risk on a young kid with very little to no experience.”

In the mid-1990s, Lester installed Friedman as the president of the Williams-Sonoma and Pottery Barn brands, the latter still a modest tabletop and accessories company that earned $50 million a year—which Friedman grew into a $1.2 billion home furnishings brand in seven years. “It really happened because I remodeled a 1,200-square-foot condo in San Francisco and didn’t know where to buy furniture,” he explains. After an interior designer quoted him $120,000—far beyond his price range—he decided on a budget of $20,000 and decided to shop for himself. “I remember ugly floral couches and all these fabrics to choose from at the Macy’s home store, and it was totally overwhelming,” he recalls. “I grew up watching Mickey make the Gap into an integrated brand, so I thought, What if I take this little tabletop business and turn it into a Gap for the home?”

The first Pottery Barn store Friedman opened was in San Francisco, in an old grocery store on Chestnut Street—“as much of a box as you can get,” he says. He hired a residential architect on a hunch, inspired by several recently opened local restaurants that had a homey feel. Based on the Chestnut Street location’s initial success, he soon built four more stores. “I’d gotten the old Pottery Barns from $600,000 to $1.2 million, so the goal was to have these new, bigger ones get to $2.5 million or $3.5 million,” he says. Each store hit $5 million to $10 million in their first year. (Friedman also developed the Williams-Sonoma Grande Cuisine stores, and spent several years conceptualizing the West Elm brand, which launched in 2002, the year after his departure.) “Gary understood the design aesthetic of the customer base he was going after,” says Shoulberg. “Pottery Barn was at the cutting edge of home furnishings retailing: The stores were classier, and the integrated merchandising, mixing big-ticket furniture with textiles and tabletop, really hadn’t been done to that degree before.”

With RH, Shoulberg argues, Friedman has continued to build upon that model. “He really did reinvent the modern home furnishings store,” he says. “There wasn’t anyone who bridged the gap between mainstream furniture retailers and to-the-trade businesses, and he fit RH into that slot, which no one had identified before. It’s exactly what he did at Pottery Barn. He’s not a one-trick pony; he’s done it twice.”

(The numbers don’t lie: On an earnings call in June, Friedman noted that the average store volume when he arrived at the company was $2.9 million; today, those stores average $15 million in the same footprint, and some galleries are pulling in $60 million annually. In December, he estimated that RH New York would become the brand’s first $100 million gallery in its second year of operation.)

Those retail-floor skills from his early days at the Gap remain deeply rooted in Friedman. “Hospitality is really treating people like they matter,” Sodikoff tells me later—and that’s exactly what Friedman does with every customer he meets while we’re at RH Yountville. During lunch, a couple at the next table over offer Friedman their congratulations.

“We want to toast to your success,” says a woman who will later tell us her name is Donna. (Friedman makes a point to ask everyone we meet what their name is when he introduces himself.) “We were just at the New York store, and we ate at the restaurant three times. I was so impressed by the quality of people you had working there.”

“It felt welcoming,” adds Donna’s husband, Rich. “It’s very rare that a sought-after New York restaurant tries to be welcoming to the guest.”

Friedman is gracious. “Oh, thank you,” he says, nodding. “That’s good to hear.”

“Our daughter lives near there in the West Village, and I do design, and I just have to say, Bravo,” she continues. “This is an amazing new journey, and I can’t wait, honestly, to just watch it. And here we are now, here, which is just incredible.”

“Oh, fantastic,” enthuses Friedman. “And where are you from?”

“Newport Beach,” the couple says in unison.

“Oh, I used to live down in Newport Beach,” replies Friedman. “I used to be the regional manager of the Gap in Southern California, and I lived right next to Hoag Hospital, at Villa Balboa. I played beach volleyball at 43rd Street way back when.”

The couple is overjoyed. “I feel like we’re sitting with Magic Johnson at the next table,” says Rich, laughing.

“Honestly, you’re such a visionary,” adds Donna. “But I don’t want to interrupt. I just wanted to say congratulations on an amazing journey.”

“Well, we try to do what we love with people we love,” says Friedman.

“It’s working,” she says. “Stick with that.”

After they leave, Friedman says, “It’s funny—that’s probably the fourth or fifth couple that I’ve met that have been in New York and here, and in such a short amount of time.” The New York gallery had only been open two months; Yountville, four weeks. “But that’s why I say it’s about being in these markets where people travel, visit, vacation, and having them experience our brand in a really authentic way.”

+ + +

Dramatic uplighting, carved columns, statement elevator shafts, age-old olive trees, gurgling fountains, opulent chandeliers in brass and crystal, and near-oversize furniture—these are the hallmarks of Friedman’s new galleries, all in RH’s indelible, immediately recognizable visual vocabulary. Perhaps none were more hard-won than RH New York, the 90,000-square-foot gallery that opened in September in the city’s Meatpacking District, in a historic building once owned by the Astor family that had most recently housed the beloved neighborhood brasserie Pastis. “A lot of galleries have been big, but this one is much gutsier and in such an iconic location,” says Gillam, who spent nearly seven years developing a plan to restore and modernize the building that was in keeping with the wants and needs of the community. The metal screen that surrounds the building’s third- and fourth-floor additions draw from the visual language of the nearby High Line, with I-beam-like shapes and rivet details.

Never one to shy away from making a splash, Friedman placed a daring four-page advertisement in the Sunday edition of The New York Times before the store’s opening that proclaimed, “The death of retailing is overrated.” Guests at the gallery’s launch party included the likes of Karlie Kloss, Ryan Seacrest and Martha Stewart.

In his earnings call that month, Friedman celebrated not only the opening of the New York gallery, but also its role as a stepping-stone to European expansion. “The customers that come to New York, especially from Europe and South America … when they see this and experience it, it’s going to echo around the world,” he said, noting that only 25 percent of global luxury fashion brand LVMH’s business comes from the U.S.—and that he and his chief real estate officer were soon headed to London, Paris and Madrid. (Friedman estimated that the company’s revenues could easily total $7 billion to $10 billion annually once it opens locations in major European cities.)

In late November, I spent a Saturday afternoon at RH New York. The store was popular almost immediately when it opened, Friedman had told me, and from what I could tell, the crowds had not abated. Though you could still find unoccupied sofas along the perimeter of each floor, the more central seating areas were packed with friends catching up over lattes or glasses of wine; people lounging solo with their laptops; entire families assembled on large sectionals, children running their hands through a nearby fountain and playing hide-and-seek amongst the armchairs; and another family cheerfully celebrating the matriarch’s birthday over beers, her cards fanned out across a cocktail table. Would-be shoppers plopped onto one sofa after another, laughing. A few couples bickered. One man conducted a mini photo shoot of his infant daughter nestled into the down of the Cloud sofa. For some, their perches seemed to be their destination; others were passing the time while waiting for a table at the restaurant upstairs.

There was shopping, too. A couple sat at the end of a long dining table showing one of the store’s designers iPhone shots of their art collection and vintage furniture. “Yes, that’s cool, you should keep it,” the designer enthused about one piece, then showed them a complementary product on her screen. The wife made a phone call. “This is taking longer than we thought, but we’re getting a lot done,” she said. Another couple walked the floor, Champagne flutes in hand, and pointed out a headboard to the designer with them. “For your master, or a guest bedroom?” she asked, adding the bed to a long spreadsheet that must have equated to at least $50,000 in sales. “We’re moving the brand from just creating and selling products to conceptualizing and selling spaces,” Friedman had told me. “It’s about beautiful spaces that make people go, ‘Gosh, I’d like my home to feel like this.’”

Given the success of the restaurant in RH Chicago, the team revisited the plans for the New York gallery to create a rooftop dining experience. Sodikoff immediately sprung into action. “When Gary let me know that he was interested in putting hospitality in the New York gallery, which wasn’t originally planned, I flew to New York, found a space that I liked, and quickly launched a small restaurant called 4 Charles Prime Rib,” he says. Though only a half-mile away in the West Village, the moody, wood-paneled 36-seat steakhouse is completely independent of RH New York, operated under Sodikoff’s restaurant group Hogsalt Hospitality—and has become a tremendous success in its own right. But the purpose from the get-go was to get boots-on-the-ground experience running a restaurant in New York. “It was small enough that I could get it open fast and sustain it as a platform to train staff and develop relationships with purveyors,” he explains. “Hogsalt can jump in, take more risks, and learn some things, and then we can leverage that platform for the hospitality at RH. We couldn’t have done what we’ve done in the past few years without building a corps of people who could inspire and train others.”

And just like RH Chicago before it, RH New York’s restaurant is already off to a roaring start; the company soon expects it to generate in excess of $15 million per year. For Friedman, the restaurant’s success has come with one not-so-savory side effect: “You wouldn’t believe the number of people texting me for reservations,” he says ruefully. He changes his voice to imitate the messages on his phone: “‘Hey, man—can you get me in?’”

At least one of RH’s next big ventures will also debut in New York—and seems likely to have the same immediate appeal. Located around the corner from the gallery on Gansevoort Street, the boutique hotel, called RH Guesthouse, is scheduled to open in the fall. (In the same way that Friedman sees galleries as fundamentally different from stores, he corrects me when I call the space a hotel. So what exactly is a guest house? “You’ll know it when you see it,” he says.)

And contrary to popular theory, RH Guesthouse will have little to no RH product inside, Friedman reveals. “People think, ‘Oh, it’ll be a showroom for your products,’ and we go, ‘No, we already have those,’” he says. “I mean, there might be a couple sconce lights [in the rooms] that we carry [in the gallery], but even the bed—I’m going to purposely design a bed for the Guesthouse that we don’t sell. It’s going to be a super-exclusive, personal space, and we’re not going to try to peddle any furniture. That’s too obvious. It’s really about positioning RH as a thought leader, a taste leader, a creative leader in the industry.”

Friedman hints at special features in the room, a stellar rooftop, a wine vault in the basement, and an iteration of Sodikoff’s famous Doughnut Vault. “Just like we redefined a food and wine experience in the Napa Valley, our first RH Guesthouse has to be like nothing anybody’s ever seen,” he says. “The goal is that the legends of hospitality—Isadore Sharp, who invented the Four Seasons; Horst Schulze, who won the Malcolm Baldrige Award twice [for] the Ritz-Carlton; Anouska Hempel, who created the Blakes Hotel in London; and Ian Schrager, who pioneered the ideal of the boutique hotel in America—if they could walk in and see it, they’d tip their hat in respect and go, ‘Wow, nice job. You’ve done things that we think are really smart.’”

+ + +

"I think you’re going to see a lot more hospitality within RH, but also with followers on other platforms trying to race to catch up,” Sodikoff tells me. “There’s this growing realization that people don’t want uncomfortable shopping experiences. They’d rather stay home. But providing an inspiring environment that fulfills you, and you might do some shopping on the side—that’s different.” His advice is much the same as his early words of caution to the RH team: It’s a difficult puzzle, and you have to be really committed to it. “Old retailing is dead,” he adds. “Whether you have food or not, having a greater hospitality lens on how to make people feel great is what defines the future of retail.”

But Friedman doesn’t seem concerned about those that will follow. “Nothing comes from, ‘How do we compete with anybody else?’” he says. “It all comes from, ‘What do we deeply believe in? What do we love? Where would we want to go? Where would we want to spend our time?’” (Possible answers to those questions can be found in some of RH’s upcoming 2019 initiatives: In addition to opening five more galleries and the Guesthouse, the company plans to reveal the first RH Beach House this spring, as well as RH Color, their take on less-neutral home furnishings, in the fall.)

“When people tell me that we’re really good at thinking outside of the box, I say no. The most creative people can look in a box that small,” says Friedman, gesturing with his hands, “and see a thousand opportunities in that box. Outside-the-box ideas might be interesting, but they’re not relevant to the problem we’re trying to solve or the thing we’re trying to do.”

He references Donna and Rich, our table neighbors at lunch. “Donna said, ‘We were in New York and it was incredible.’ Why? Because she believes what we believe, she loves what we love. All of what we do is based in beliefs—and it doesn’t have to be for everybody. If some people go, ‘Oh, I don’t like it, there’s no color or prints.’ That’s OK, go shop somewhere else. There are some people who are going to hate our food. They say it is really basic—a burger and a shaved rib-eye sandwich, truffle grilled cheese, roasted chicken, and Dover sole. It’s a wonderful execution of our favorite dishes, but if you don’t like this food, that’s OK. Go eat somewhere else.”

“It’s when you try to get to the middle ground that you’re not anything to anybody. You’re just kind of a blur. You’re not memorable at all.”

Correction: May 11, 2020

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Horst Schulze had passed away. While the German actor and opera singer by that name died in October 2018, the hotelier referenced by Friedman is still alive.